- City Departments

-

-

Community Development

-

Community Response

-

Convention and Cultural Services

-

Finance

-

Fire Department

-

Human Resources

-

Information Technology

-

Mayor and Council

-

Office of Public Safety Accountability

-

Office of the City Attorney

-

Office of the City Auditor

-

Office of the City Clerk

-

Office of the City Manager

-

Office of the City Treasurer

-

Police Department

-

Public Works

-

Utilities

-

Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

-

- Browse by categories

-

-

hiking Activities

-

pets Animals & Pets

-

domain_add Building & Planning

-

store Business

-

account_tree City Administration

-

category City Assets & Data

-

explore City Regions

-

diversity_4 Community Support

-

theater_comedy Culture & History

-

business_center Employment

-

directions Infrastructure

-

gavel Law, Code & Compliance

-

payments Money

-

park Outdoors & Sustainability

-

local_police Safety

-

directions_car Transportation

-

delete_sweep Utility Services

-

Use the menus above to navigate by City Departments or Categories.

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Home

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Community Engagement

- Community Engagement

- About YPCE

- Hart Senior Center

- Recreation

- Youth Workforce Development

- Older Adult Services

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Long Range

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Home

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- About YPCE

- Older Adult Services

- Recreation

- Home

- Parking

- Innovation and Grants

- Aquatics

- CCS Partners

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Community Engagement

- District 7 - Rick Jennings

- Request a Permit

- CCS Partners

- Fire Department

- About YPCE

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- River District Specific Plan

- Convention and Cultural Services

- CCS Partners

- Emergency Management

- CCS Partners

- Commercial Waste Services

- Home

- Recreation

- Access Leisure

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Specialty Parks

- Specialty Parks

- Permits for YPCE

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Aquatics

- Recreation

- Home

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Community Development

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Specialty Parks

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Street Landscape Maintenance

- Accessory Dwelling Units

- City Government

- Community Development

- Building

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Business Waste Requirements

- Commercial Waste Services

- Maintenance Services

- Procurement Services Division

- Parks

- Utilities

- Public Works

- Engineering

- Fire Prevention

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Engineering

- Home

- Public Works

- Housing

- Engineering

- Housing

- Planning

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Fire Prevention

- Fire Prevention

- Community Development

- Community Development

- Building Programs

- Community Development

- Transportation

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Planning

- Planning

- Planning

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Planning

- Planning

- Parks

- Community Development

- Community Development

- Planning

- List of City Manager's Office Projects and Programs

- Public Works

- Planning

- Planning

- Public Works

- Transportation

- Planning

- Planning

- Engineering

- 102-Acre Site

- Community Development Meetings and Hearings

- Major Planning Projects

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Major Planning Projects

- Planning

- City Government

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Code Compliance

- Revenue Division

- Business

- Office of the City Manager

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Business

- Business

- Procurement Services Division

- Revenue Division

- Business

- Revenue Division

- Major Planning Projects

- City Auditor Reports

- City Auditor Reports

- Cannabis Management

- Cannabis Management

- Cannabis Management

- Business Operations Tax

- Cannabis Management

- Office of the City Manager

- Cannabis Management

- City Auditor Reports

- Cannabis Management

- Major Planning Projects

- Parking

- COVID-19 Relief & Recovery

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Community Engagement

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Office of the City Manager

- Business

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Office of the City Manager

- Business

- Finance

- Accounting Division

- Police Services

- Procurement Services Division

- City Government

- Code Compliance Programs

- Code Compliance Programs

- Commercial Waste Services

- Procurement Services Division

- Procurement Services Division

- Home

- Commercial Waste Services

- Procurement Services Division

- Finance

- Finance

- Procurement Services Division

- Procurement Services Division

- Office of the City Auditor

- Police Transparency

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Accounting Division

- Office of the City Clerk

- Home

- About YPCE

- Arts and Culture

- Diversity and Equity

- Records Management

- Office of the City Auditor

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- District 2 - Roger Dickinson

- City Auditor Reports

- Office of the City Clerk

- About YPCE

- Police Transparency

- Home

- Records Management

- Office of the City Manager

- Office of the City Manager

- Neighborhood Directory

- Neighborhood Directory

- Community Engagement

- Office of the City Clerk

- Office of the City Manager

- Innovation and Grants

- Office of the City Manager

- Office of the City Manager

- Office of the City Manager

- Home

- River District Specific Plan

- City Government

- Engineering

- City Government

- Long Range

- City Government

- City Government

- City Government

- City Government

- Information Technology

- Camp Sacramento

- Parking

- About YPCE

- Finance

- Drinking Water Quality

- Utilities

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- Pay Your Utility Bill

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Marina

- Police Services

- Contact Us

- Police Services

- Office of the City Clerk

- Home

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Office of the City Clerk

- Mayor and Council

- Home

- Diversity and Equity

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- About the City Attorney's Office

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Police Department

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- Police Department

- City Government

- Office of the City Auditor

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- 102-Acre Site

- 102-Acre Site

- 102-Acre Site

- Public Works

- Construction & Demolition Recycling

- About SPD

- Facilities & Real Property Management

- Public Works

- Adult Sports Activities and Resources

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Fleet Services

- Public Works

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- General Plans

- Police Transparency

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Legislative Management

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Home

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- Office of the City Clerk

- Police Services

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- About the City Attorney's Office

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Police Department

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- Police Department

- City Government

- Office of the City Auditor

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- City Elections

- Community Resources and Financial Empowerment

- Long Range

- Community Engagement

- Youth Workforce Development

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Major Planning Projects

- Public Art Projects

- Engineering

- 102-Acre Site

- Community Development Meetings and Hearings

- Major Planning Projects

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Major Planning Projects

- Planning

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Specialty Parks

- Long Range

- City Government

- List of City Manager's Office Projects and Programs

- Parking

- Transportation Projects

- About YPCE

- Home

- Engineering Programs & Services

- About OAC

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Maintenance Services

- City Government

- Older Adult Services

- Housing

- Home

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- About YPCE

- Older Adult Services

- Recreation

- Home

- 102-Acre Site

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- Long Range

- City Auditor Reports

- Priority Projects/Investments

- Community Engagement

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Diversity and Equity

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Transportation

- Responding to Homelessness

- Office of the City Manager

- District 5 - Caity Maple

- Office of the City Manager

- Safety and Crime Prevention Tips

- Youth Workforce Development

- Police Department

- Community Development Meetings and Hearings

- River District Specific Plan

- Diversity and Equity

- Older Adult Services

- Vision Zero: Transportation Safety

- About Access Leisure

- Access Leisure Sports

- Access Leisure Sports

- Cannabis Management

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Human Resources

- Financial Empowerment

- Home

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Police Community Programs

- Community Response

- Community Response

- Workforce Development

- Police Community Programs

- Community Response

- Community Response

- Office of the City Manager

- Planning

- Housing

- Housing Development Toolkit

- City and County Partnership

- Housing Development Toolkit

- Housing

- Housing

- City and County Partnership

- Code Compliance

- Housing

- Revenue Division

- Priority Projects/Investments

- Housing

- Long Range

- About YPCE

- Older Adult Services

- Recreation

- Older Adult Services

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Older Adult Services

- Housing

- Home

- District 5 - Caity Maple

- About the Office of the City Auditor

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Animal Care

- District 7 Resources

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Community Engagement

- Police Community Programs

- About YPCE

- Police Department

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Specialty Parks

- Aquatics Programs

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- District 7 Resources

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- CCS Partners

- Join Sacramento Fire

- About YPCE

- Aquatics Programs

- Recreation

- Aquatics

- City Auditor Reports

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Police Community Programs

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Public Art Projects

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Police Community Programs

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Home

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Home

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Parking

- Innovation and Grants

- Aquatics

- CCS Partners

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Community Engagement

- District 7 - Rick Jennings

- Request a Permit

- CCS Partners

- Fire Department

- About YPCE

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- River District Specific Plan

- Convention and Cultural Services

- CCS Partners

- Emergency Management

- CCS Partners

- Commercial Waste Services

- Home

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- Convention and Cultural Services

- About the City Attorney's Office

- Specialty Parks

- Planning

- Public Art Projects

- About Sacramento Fire

- CCS Partners

- Public Works

- Police Department

- About Access Leisure

- Access Leisure Sports

- Access Leisure Sports

- Cannabis Management

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Human Resources

- Financial Empowerment

- Home

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Police Community Programs

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Home

- Human Resources

- Payroll Division

- Camp Sacramento

- HR Documents & Resources

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Home

- District 7 Resources

- Fire Department

- Leisure Enrichment

- Employee & Retiree Benefits

- Youth Workforce Development

- Sacramento START

- Police Services

- District 5 - Caity Maple

- About the Office of the City Auditor

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Animal Care

- District 7 Resources

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Community Engagement

- Police Community Programs

- About YPCE

- Police Department

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Youth Workforce Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Utilities

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- City Government

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Home

- Fire Operations

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Collection Calendar

- City Government

- Information Technology

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Home

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Finance

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Building Programs

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Office of the City Manager

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Safety Tips

- Construction Coordination

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Utilities

- Public Works

- Maintenance Services

- Public Works

- Police Community Programs

- Home

- Survey Services

- Maintenance Services

- Maintenance Services

- Maintenance Services

- Curbside Collection Services & Rates

- Tree Permits and Ordinances

- Public Works

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Engineering

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Park Planning & Development

- Parks

- Public Works

- Transportation Projects

- Parks

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Home

- Community Development

- Community Development

- Code Compliance

- Code Compliance

- Community Development

- Code Compliance

- Code Compliance

- Community Development

- Fire Prevention

- Construction & Demolition Recycling

- Code Compliance

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Code Compliance

- Franchise Waste Haulers

- Residential Permit Parking (RPP)

- Code Compliance

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Fire Prevention

- Fire Prevention

- Commercial Waste Services

- Cannabis Management

- City Government

- Commercial Waste Services

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Disabled Person Parking

- Fire Code Enforcement

- Police Transparency

- Commercial Waste Services

- Contact Parking Services

- Residential Permit Parking (RPP)

- Community Development

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Public Records

- Code Compliance

- Cannabis Management

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Engineering

- Request a Permit

- Housing Development Incentives

- Arts and Culture

- Housing Development Incentives

- Public Works

- Public Works

- Building

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Building

- Request a Permit

- Public Works

- Revenue Division

- Revenue Division

- Commercial Waste Services

- Building Programs

- Urban Forestry

- Planning

- Finance

- Accounting Division

- Home

- Accounting Division

- City Auditor Reports

- Payroll Division

- Curbside Collection Services & Rates

- Office of the City Manager

- Finance

- Budget Division

- Budget Division

- Home

- Access Leisure

- Climate and Sustainability Planning

- Pay Your Utility Bill

- Hart Senior Center

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Discount Deals

- Water Conservation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Aquatics

- Finance

- Utility User Tax

- Recreation

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Home

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Parking

- COVID-19 Relief & Recovery

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Community Engagement

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Office of the City Manager

- Business

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- CORE

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Stormwater Quality

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Economic Gardening

- Arts and Culture

- Forward Together Pilot Grant for North Sacramento

- Innovation and Grants

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Innovation and Grants

- Innovation and Grants

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About OAC

- Engineering

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Home

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Finance

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Building Programs

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Home

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Building

- Cannabis Business Operating Permits

- Revenue Division

- Development Standards

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Development Standards

- Emergency Medical Services

- Finance

- Community Engagement

- Marina

- Household Hazardous Waste

- Public Works

- Community Development

- Revenue Division

- Utilities

- City Government

- Finance

- Animal Care

- Home

- Development Standards

- Marina

- Revenue Division

- Permits for YPCE

- Revenue Division

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Home

- Workforce Development

- List of City Manager's Office Projects and Programs

- About YPCE

- Revenue Division

- Budget Division

- Revenue Division

- Revenue Division

- Transportation

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Projects

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Housing

- Public Works

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Public Works

- Home

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Street Landscape Maintenance

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Public Works

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Climate and Sustainability Planning

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Planning

- Fleet Services

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Procurement Services Division

- Business Waste Requirements

- Permit Services

- Utilities

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Utilities

- Recreation

- About YPCE

- Public Works

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- Public Art Projects

- Commercial Waste Services

- Permits for YPCE

- About YPCE

- Home

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Recreation

- Access Leisure

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Specialty Parks

- Specialty Parks

- Permits for YPCE

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Aquatics

- Recreation

- Home

- Park Planning & Development

- Parks

- Public Works

- Transportation Projects

- Parks

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Urban Forestry

- Parks

- Public Works

- Parks

- Home

- Urban Forestry

- Urban Forestry

- Urban Forestry

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Maintenance Services

- Safety Tips

- Office of the City Manager

- Specialty Parks

- Community Response

- Community Response

- Home

- Office of the City Manager

- Contact Us

- Contact Us

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Police Services

- Fire Prevention

- Crime and Safety

- Police Services

- Crime and Safety

- Pay Your Utility Bill

- Crime and Safety

- Office of the City Auditor

- City Auditor Reports

- Fire Prevention

- Office of the City Manager

- Fire Department

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Crime and Safety

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Emergency Management

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Home

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Home

- Fire Department

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Fire Prevention

- Fire Prevention

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Department

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Public Information Office

- Police Services

- Home

- Police Department

- Home

- Police Department

- Police Department

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Department

- Emergency Management

- Police Department

- Information Technology

- Flood Preparedness

- Fire Department

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Office of the City Manager

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Safety Tips

- Safety Tips

- Office of the City Manager

- Specialty Parks

- Transportation

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Projects

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Housing

- Public Works

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Public Works

- Home

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Technology

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Parking

- Fleet Services

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Police Services

- Marina

- Marina

- Public Works

- Housing

- Home

- Public Works

- Curbside Collection Services & Rates

- Sacramento Valley Station

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Projects

- Public Works

- Long Range

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation

- Public Works

- Home

- Public Works

- File a Police Report

- Public Works

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Engineering

- Transportation

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Utilities

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Public Works

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Public Works

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Home

- City Departments

-

-

Community Development

-

Community Response

-

Convention and Cultural Services

-

Finance

-

Fire Department

-

Human Resources

-

Information Technology

-

Mayor and Council

-

Office of Public Safety Accountability

-

Office of the City Attorney

-

Office of the City Auditor

-

Office of the City Clerk

-

Office of the City Manager

-

Office of the City Treasurer

-

Police Department

-

Public Works

-

Utilities

-

Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

-

- Browse by categories

-

-

hiking Activities

-

pets Animals & Pets

-

domain_add Building & Planning

-

store Business

-

account_tree City Administration

-

category City Assets & Data

-

explore City Regions

-

diversity_4 Community Support

-

theater_comedy Culture & History

-

business_center Employment

-

directions Infrastructure

-

gavel Law, Code & Compliance

-

payments Money

-

park Outdoors & Sustainability

-

local_police Safety

-

directions_car Transportation

-

delete_sweep Utility Services

-

Use the menus above to navigate by City Departments or Categories.

You can also use the Search function below to find specific content on our site.

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Home

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Community Engagement

- Community Engagement

- About YPCE

- Hart Senior Center

- Recreation

- Youth Workforce Development

- Older Adult Services

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Long Range

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Home

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- About YPCE

- Older Adult Services

- Recreation

- Home

- Parking

- Innovation and Grants

- Aquatics

- CCS Partners

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Community Engagement

- District 7 - Rick Jennings

- Request a Permit

- CCS Partners

- Fire Department

- About YPCE

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- River District Specific Plan

- Convention and Cultural Services

- CCS Partners

- Emergency Management

- CCS Partners

- Commercial Waste Services

- Home

- Recreation

- Access Leisure

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Specialty Parks

- Specialty Parks

- Permits for YPCE

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Aquatics

- Recreation

- Home

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Community Development

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Specialty Parks

- Animal Care

- Animal Care

- Street Landscape Maintenance

- Accessory Dwelling Units

- City Government

- Community Development

- Building

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Business Waste Requirements

- Commercial Waste Services

- Maintenance Services

- Procurement Services Division

- Parks

- Utilities

- Public Works

- Engineering

- Fire Prevention

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Building

- Engineering

- Home

- Public Works

- Housing

- Engineering

- Housing

- Planning

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Fire Prevention

- Fire Prevention

- Community Development

- Community Development

- Building Programs

- Community Development

- Transportation

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Planning

- Planning

- Planning

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Planning

- Planning

- Parks

- Community Development

- Community Development

- Planning

- List of City Manager's Office Projects and Programs

- Public Works

- Planning

- Planning

- Public Works

- Transportation

- Planning

- Planning

- Engineering

- 102-Acre Site

- Community Development Meetings and Hearings

- Major Planning Projects

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Major Planning Projects

- Planning

- City Government

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Code Compliance

- Revenue Division

- Business

- Office of the City Manager

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Business

- Business

- Procurement Services Division

- Revenue Division

- Business

- Revenue Division

- Major Planning Projects

- City Auditor Reports

- City Auditor Reports

- Cannabis Management

- Cannabis Management

- Cannabis Management

- Business Operations Tax

- Cannabis Management

- Office of the City Manager

- Cannabis Management

- City Auditor Reports

- Cannabis Management

- Major Planning Projects

- Parking

- COVID-19 Relief & Recovery

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Community Engagement

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Office of the City Manager

- Business

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Office of the City Manager

- Business

- Finance

- Accounting Division

- Police Services

- Procurement Services Division

- City Government

- Code Compliance Programs

- Code Compliance Programs

- Commercial Waste Services

- Procurement Services Division

- Procurement Services Division

- Home

- Commercial Waste Services

- Procurement Services Division

- Finance

- Finance

- Procurement Services Division

- Procurement Services Division

- Office of the City Auditor

- Police Transparency

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Accounting Division

- Office of the City Clerk

- Home

- About YPCE

- Arts and Culture

- Diversity and Equity

- Records Management

- Office of the City Auditor

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- District 2 - Roger Dickinson

- City Auditor Reports

- Office of the City Clerk

- About YPCE

- Police Transparency

- Home

- Records Management

- Office of the City Manager

- Office of the City Manager

- Neighborhood Directory

- Neighborhood Directory

- Community Engagement

- Office of the City Clerk

- Office of the City Manager

- Innovation and Grants

- Office of the City Manager

- Office of the City Manager

- Office of the City Manager

- Home

- River District Specific Plan

- City Government

- Engineering

- City Government

- Long Range

- City Government

- City Government

- City Government

- City Government

- Information Technology

- Camp Sacramento

- Parking

- About YPCE

- Finance

- Drinking Water Quality

- Utilities

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- Pay Your Utility Bill

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Marina

- Police Services

- Contact Us

- Police Services

- Office of the City Clerk

- Home

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Office of the City Clerk

- Mayor and Council

- Home

- Diversity and Equity

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- About the City Attorney's Office

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Police Department

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- Police Department

- City Government

- Office of the City Auditor

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- 102-Acre Site

- 102-Acre Site

- 102-Acre Site

- Public Works

- Construction & Demolition Recycling

- About SPD

- Facilities & Real Property Management

- Public Works

- Adult Sports Activities and Resources

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Fleet Services

- Public Works

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- Director Hearings

- General Plans

- Police Transparency

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Legislative Management

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Home

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- Office of the City Clerk

- Police Services

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- About the City Attorney's Office

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Police Department

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- Office of Public Safety Accountability

- Police Department

- City Government

- Office of the City Auditor

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Mayor and Council

- Maps and Geographic Information Systems

- City Elections

- Community Resources and Financial Empowerment

- Long Range

- Community Engagement

- Youth Workforce Development

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Major Planning Projects

- Public Art Projects

- Engineering

- 102-Acre Site

- Community Development Meetings and Hearings

- Major Planning Projects

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Major Planning Projects

- Planning

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Specialty Parks

- Long Range

- City Government

- List of City Manager's Office Projects and Programs

- Parking

- Transportation Projects

- About YPCE

- Home

- Engineering Programs & Services

- About OAC

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Maintenance Services

- City Government

- Older Adult Services

- Housing

- Home

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- About YPCE

- Older Adult Services

- Recreation

- Home

- 102-Acre Site

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- Long Range

- City Auditor Reports

- Priority Projects/Investments

- Community Engagement

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Diversity and Equity

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Transportation

- Responding to Homelessness

- Office of the City Manager

- District 5 - Caity Maple

- Office of the City Manager

- Safety and Crime Prevention Tips

- Youth Workforce Development

- Police Department

- Community Development Meetings and Hearings

- River District Specific Plan

- Diversity and Equity

- Older Adult Services

- Vision Zero: Transportation Safety

- About Access Leisure

- Access Leisure Sports

- Access Leisure Sports

- Cannabis Management

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Human Resources

- Financial Empowerment

- Home

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Police Community Programs

- Community Response

- Community Response

- Workforce Development

- Police Community Programs

- Community Response

- Community Response

- Office of the City Manager

- Planning

- Housing

- Housing Development Toolkit

- City and County Partnership

- Housing Development Toolkit

- Housing

- Housing

- City and County Partnership

- Code Compliance

- Housing

- Revenue Division

- Priority Projects/Investments

- Housing

- Long Range

- About YPCE

- Older Adult Services

- Recreation

- Older Adult Services

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Older Adult Services

- Housing

- Home

- District 5 - Caity Maple

- About the Office of the City Auditor

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Animal Care

- District 7 Resources

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Community Engagement

- Police Community Programs

- About YPCE

- Police Department

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Specialty Parks

- Aquatics Programs

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- District 7 Resources

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- CCS Partners

- Join Sacramento Fire

- About YPCE

- Aquatics Programs

- Recreation

- Aquatics

- City Auditor Reports

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Police Community Programs

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Public Art Projects

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Police Community Programs

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Home

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Home

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Arts and Culture

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Parking

- Innovation and Grants

- Aquatics

- CCS Partners

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Community Engagement

- District 7 - Rick Jennings

- Request a Permit

- CCS Partners

- Fire Department

- About YPCE

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- River District Specific Plan

- Convention and Cultural Services

- CCS Partners

- Emergency Management

- CCS Partners

- Commercial Waste Services

- Home

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- Convention and Cultural Services

- About the City Attorney's Office

- Specialty Parks

- Planning

- Public Art Projects

- About Sacramento Fire

- CCS Partners

- Public Works

- Police Department

- About Access Leisure

- Access Leisure Sports

- Access Leisure Sports

- Cannabis Management

- Office of the City Auditor

- Office of the City Auditor

- Human Resources

- Financial Empowerment

- Home

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Police Community Programs

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Home

- Human Resources

- Payroll Division

- Camp Sacramento

- HR Documents & Resources

- Human Resources

- Human Resources

- Home

- District 7 Resources

- Fire Department

- Leisure Enrichment

- Employee & Retiree Benefits

- Youth Workforce Development

- Sacramento START

- Police Services

- District 5 - Caity Maple

- About the Office of the City Auditor

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Animal Care

- District 7 Resources

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Community Engagement

- Police Community Programs

- About YPCE

- Police Department

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Youth Workforce Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Utilities

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- City Government

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Home

- Fire Operations

- Information Technology

- Information Technology

- Collection Calendar

- City Government

- Information Technology

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Home

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Finance

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Building Programs

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Office of the City Manager

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Safety Tips

- Construction Coordination

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Utilities

- Public Works

- Maintenance Services

- Public Works

- Police Community Programs

- Home

- Survey Services

- Maintenance Services

- Maintenance Services

- Maintenance Services

- Curbside Collection Services & Rates

- Tree Permits and Ordinances

- Public Works

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Engineering

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Park Planning & Development

- Parks

- Public Works

- Transportation Projects

- Parks

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Home

- Community Development

- Community Development

- Code Compliance

- Code Compliance

- Community Development

- Code Compliance

- Code Compliance

- Community Development

- Fire Prevention

- Construction & Demolition Recycling

- Code Compliance

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Code Compliance

- Franchise Waste Haulers

- Residential Permit Parking (RPP)

- Code Compliance

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Fire Prevention

- Fire Prevention

- Commercial Waste Services

- Cannabis Management

- City Government

- Commercial Waste Services

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Disabled Person Parking

- Fire Code Enforcement

- Police Transparency

- Commercial Waste Services

- Contact Parking Services

- Residential Permit Parking (RPP)

- Community Development

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Public Records

- Code Compliance

- Cannabis Management

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Engineering

- Request a Permit

- Housing Development Incentives

- Arts and Culture

- Housing Development Incentives

- Public Works

- Public Works

- Building

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Locate & Grow in Sacramento

- Building

- Request a Permit

- Public Works

- Revenue Division

- Revenue Division

- Commercial Waste Services

- Building Programs

- Urban Forestry

- Planning

- Finance

- Accounting Division

- Home

- Accounting Division

- City Auditor Reports

- Payroll Division

- Curbside Collection Services & Rates

- Office of the City Manager

- Finance

- Budget Division

- Budget Division

- Home

- Access Leisure

- Climate and Sustainability Planning

- Pay Your Utility Bill

- Hart Senior Center

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Discount Deals

- Water Conservation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Aquatics

- Finance

- Utility User Tax

- Recreation

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Home

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Parking

- COVID-19 Relief & Recovery

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Community Engagement

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Office of the City Manager

- Business

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Innovation and Economic Development

- Business

- Innovation and Economic Development

- CORE

- Convention and Cultural Services

- Stormwater Quality

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Funding and Grants for Arts and Culture

- Economic Gardening

- Arts and Culture

- Forward Together Pilot Grant for North Sacramento

- Innovation and Grants

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Innovation and Grants

- Innovation and Grants

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About OAC

- Engineering

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Home

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Finance

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Building Programs

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Home

- Office of the City Treasurer

- Building

- Cannabis Business Operating Permits

- Revenue Division

- Development Standards

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Development Standards

- Emergency Medical Services

- Finance

- Community Engagement

- Marina

- Household Hazardous Waste

- Public Works

- Community Development

- Revenue Division

- Utilities

- City Government

- Finance

- Animal Care

- Home

- Development Standards

- Marina

- Revenue Division

- Permits for YPCE

- Revenue Division

- Infrastructure Finance Division

- Home

- Workforce Development

- List of City Manager's Office Projects and Programs

- About YPCE

- Revenue Division

- Budget Division

- Revenue Division

- Revenue Division

- Transportation

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Projects

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Housing

- Public Works

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Public Works

- Home

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Street Landscape Maintenance

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Public Works

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Climate and Sustainability Planning

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Planning

- Fleet Services

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Procurement Services Division

- Business Waste Requirements

- Permit Services

- Utilities

- Climate Action and Sustainability

- Utilities

- Recreation

- About YPCE

- Public Works

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- Public Art Projects

- Commercial Waste Services

- Permits for YPCE

- About YPCE

- Home

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Recreation

- Access Leisure

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Recreation

- Specialty Parks

- Specialty Parks

- Permits for YPCE

- Recreation

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- About YPCE

- Youth, Parks, & Community Enrichment

- Aquatics

- Recreation

- Home

- Park Planning & Development

- Parks

- Public Works

- Transportation Projects

- Parks

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Transportation Projects

- Urban Forestry

- Parks

- Public Works

- Parks

- Home

- Urban Forestry

- Urban Forestry

- Urban Forestry

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Maintenance Services

- Safety Tips

- Office of the City Manager

- Specialty Parks

- Community Response

- Community Response

- Home

- Office of the City Manager

- Contact Us

- Contact Us

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Crime and Safety

- Police Services

- Fire Prevention

- Crime and Safety

- Police Services

- Crime and Safety

- Pay Your Utility Bill

- Crime and Safety

- Office of the City Auditor

- City Auditor Reports

- Fire Prevention

- Office of the City Manager

- Fire Department

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Crime and Safety

- Join Sacramento Fire

- Emergency Management

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Home

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Fire Department

- Home

- Fire Department

- Fire Prevention

- Contact CDD

- Building

- Fire Prevention

- Fire Prevention

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Request a Permit

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Department

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Public Information Office

- Police Services

- Home

- Police Department

- Home

- Police Department

- Police Department

- Request a Permit

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Services

- Police Department

- Emergency Management

- Police Department

- Information Technology

- Flood Preparedness

- Fire Department

- District 1 - Lisa Kaplan

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Office of the City Manager

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Safety Tips

- Safety Tips

- Office of the City Manager

- Specialty Parks

- Transportation

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Projects

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Housing

- Public Works

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Public Works

- Home

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Technology

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Parking

- Fleet Services

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Police Services

- Marina

- Marina

- Public Works

- Housing

- Home

- Public Works

- Curbside Collection Services & Rates

- Sacramento Valley Station

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation Projects

- Public Works

- Long Range

- Current Transportation Efforts, Plans and Programs

- Transportation

- Public Works

- Home

- Public Works

- File a Police Report

- Public Works

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Transportation

- Engineering

- Transportation

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Home

- Utilities

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Public Works

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Public Works

- Climate Action Initiatives

- Recycling & Solid Waste

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Utilities

- Stormwater Quality

- Home

Search for content

- Home

- ...

- Housing

- Sacramento for All: Housing Education Resource Center

- 1. Sacramento's Housing History

SITE NAVIGATION

1. Sacramento's Housing History

Since Sacramento’s establishment as a frontier outpost in the middle of the 18th century to the present-day, the complexities of housing affordability and gentrification have revealed the ups and downs of economic forces, government policies, and community advocacy that have made Sacramento the place that it is today. This timeline provides a historical overview of the forces that have affected housing outcomes in Sacramento over many decades. The majority of the historical accounts below aim to summarize key sections of Race & Place in Sacramento (Report), a report conducted by Dr. Jesus Hernandez as part of the City’s Environmental Justice Element for the 2040 General Plan. JCH Research, the sole originator of the Report, assumes all responsibility for any errors and omissions as well as the content of the Report.

open_in_full

open_in_full

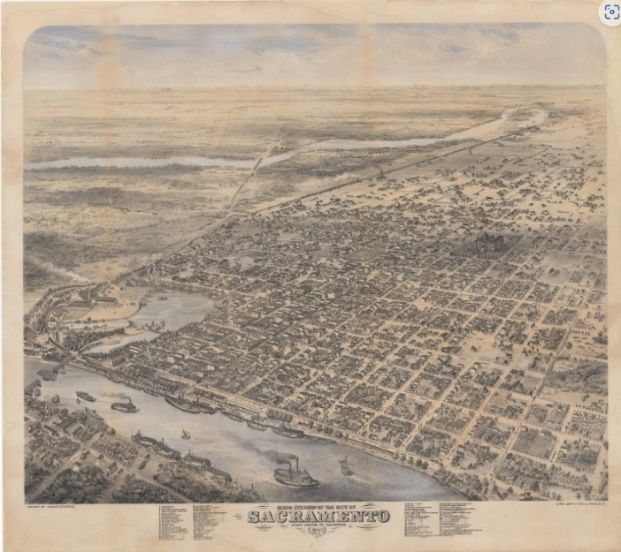

Bird's eye view of the City of Sacramento in 1870. Get a closer look here

1840-1899 The Early Years

For centuries, Sacramento was and remains the ancestral homelands to the Nisenan people, the Southern Maidu, Valley and Plains Miwok, Patwin Wintun people, and the people of the Wilton Rancheria. In 1841, Sacramento was settled by John A. Sutter and became a stable frontier outpost a few years later. Sutter had an official plan for the city prepared and the citizens of Sacramento adopted a City charter in 1849. In 1850, Sacramento became the first incorporated city in California.

The city became the valley’s major transportation hub and the official state capital by 1860. During this time, Sacramento’s population grew rapidly from 9,087 in 1850 to 45,915 in 1900. This rapid growth led to overcrowded housing followed by public health and sanitation problems due to a lack of infrastructure. Additionally, the State Constitution at this time restricted Chinese immigrants from owning land and property, which marked the first legal effort to directly intervene on where people could live solely based on race (Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882).

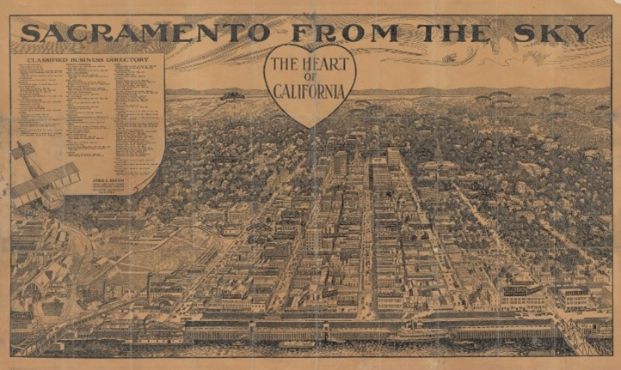

1900-1945: Housing Boom, Great Depression, and Beginnings of Redlining

In 1911, Sacramento had eight streetcar lines and the city annexed 9.4 square miles of land, which included the neighborhoods now known as Land Park, Curtis Park, Tahoe Park, and East Sacramento. At this time, the California Alien Land Law of 1913 was passed and marked the beginning of the widespread use of racial restrictions on land and property ownership, preventing many people from being able to reside in these neighborhoods. Access to mortgages came through local realtors who were committed to the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ race-based guidelines that excluded people of color (POC) from owning property.

open_in_full

open_in_full

Sacramento from the sky, the Heart of California Get a closer look here

open_in_full

open_in_full

At the end of the Sacramento housing boom from 1925 to 1929, the Great Depression triggered a wave of foreclosures which left many new homeowners needing to refinance. The rollout of federal refinance programs in 1934 helped many avoid foreclosures through assistance such as the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), which gave homeowners long-term loans that replaced the short-term, high interest rate financing previously offered by local realtors. The abundant supply of mortgage credit led to increases in housing prices and speculation on the part of real estate investors with a surge in construction between 1936 and 1940. At this time, the use of race covenants (legal deeds which prohibited the sale of property to POC) as a condition of approval was mandated by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). This led to a sustainable home lending financing network that was solely available to white home buyers, as POC were ruled categorically ineligible for financing.

open_in_full

open_in_full

During the post-Depression suburban housing boom, federal housing credit eligibility guidelines prevented the flow of housing capital to racially integrated neighborhoods. HOLC Residential Security Maps identified the location of residents by race and ethnicity and ranked each neighborhood according to the perceived risk for mortgage default. The West End (known as downtown today) was rated the most unsuitable for mortgage lending in Sacramento. The redlining of the West End restricted existing POC property owners from participating in conventional real estate market exchanges and led to a drastic decline in the value of redlined real estate. Due to property owners’ inability to finance repairs, owners resorted to converting homes into multiple units to earn more rent to compensate for lost value.

These strategically enforced racial restrictions on residency allowed landlords to capitalize on market constraints by renting converted units at a much higher cost to POC who were unable to leave the neighborhood. Converting properties to higher density, coupled with the lack of repairs by absentee landlords, accelerated the deterioration of the area’s residential quality.

In 1945, California passed the Community Redevelopment Act, which called for the rebuilding of central business districts through the formation of local redevelopment agencies (RDA). The Act authorized RDAs to acquire blighted properties by means of governmental powers and clear them of existing buildings and residents. The land would be offered to private enterprise for redevelopment to rebuild the area for industry or housing in accordance with the local RDA’s general plan.

1949-1974: Urban Renewal and Gentrification

The Federal Housing Act of 1949 focused on eliminating substandard living conditions through the clearance of central-city slums and provided federal subsidies for cities attempting to remedy housing shortages. The Act aimed to improve the housing stock in “blighted” communities and required that redevelopment projects be predominantly residential. Revisions to the Act in 1954 weakened the requirement of predominantly residential redevelopment projects, allowing federal funds to be used towards commercial projects. As a result, neighborhoods that had primarily low-income housing before redevelopment were converted into areas of commercial office space.

open_in_full

open_in_full

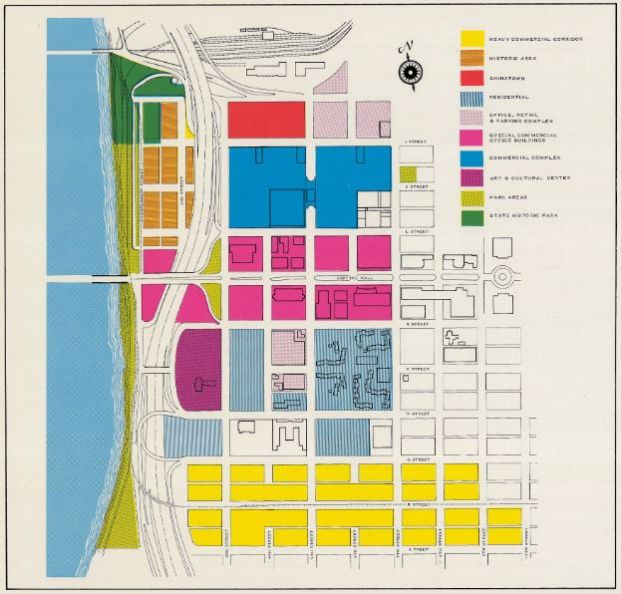

A project map for the urban renewal plans of the Redevelopment Agency of the City of Sacramento from 1968. Get a closer look here.

In Sacramento, as highlighted in the Race & Place in Sacramento report, a partnership between the city redevelopment agency and Sacramento’s commercial real estate industry functioned to reclaim segregated central-city space, which remained devalued through previous market practices of mortgage redlining and racially restrictive covenants. While covenants and redlining provided the foundation for segregation and divestment, federally funded central city redevelopment programs provided the means to shift possession of racially segregated space to private development, leading to the subsequent gentrification of neighborhoods and displacement of ethnic enclaves from 1950 to 1970. The Report cites research that more than an estimated 8,500 people were displaced from the West End as a result of urban renewal projects in Sacramento.

Despite changes to FHA guidelines in 1950, which no longer permitted the use of race covenants in considering loan approvals, POC borrowers were not afforded the opportunity to meet the qualifications of the lender or FHA because builders refused to accept their credit applications. In 1965, the Sacramento Committee for Fair Housing conducted a survey focused on the rental market in the communities of Citrus Heights, Fair Oaks, Carmichael, Arden, Rancho Cordova, Orangevale and Folsom, which showed that nine out of ten landlords refused to accept Black renters. In 1968, the federal Fair Housing Act was signed into law, prohibiting discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, sex, handicap and family status.

1975-2015: Segregation and Foreclosure Waves

As highlighted in the Report, by 1975, the combination of public housing policy, urban planning and realtor gatekeeping shifted the bulk of Downtown’s lower income POC residents to Oak Park, Fruitridge Manor, Meadowview, and Glen Elder to the south and Del Paso Heights, Gardenland, Northgate, and North Highlands to the north.

Although the Supreme Court effectively invalidated the use of race covenants in 1948 (Shelley v. Kraemer, 1948), the use of race in determining property values for bank appraisals continued until 1977. Congress passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974 to make it illegal for creditors to discriminate based on race. However, redlining continued in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods, and in 1977, the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 was enacted to prevent redlining and encourage banks to help meet the credit needs of all communities, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

A 1977 report by the Department of Savings and Loan (DSL) identified Sacramento County as one of the metropolitan areas in the state where large-scale redlining was taking place. As highlighted in the Report, the DSL data helped uncover how two distinct housing geographies emerged in the Sacramento area during the 1970s. One area consisted of race covenants, census tracts with unrestricted access to housing credit and race-based realtor gatekeeping. And the other, a new area where people of color displaced by Downtown redevelopment and pushed by realtor gatekeeping, experienced a new episode of mortgage redlining where they were kept from obtaining mortgage credit.

Additionally, a wave of FHA foreclosures during the late 1980s and early 1990s along with the subprime foreclosure wave of the 2000’s, kept home prices depressed. This created a Rent Gap (the difference between the rent obtained and the potential rent possible if it were developed to its best use) that led to the rise in speculative real estate investment. The Subprime Loan Crisis during 2003-2007 triggered a wave of foreclosures and property loss for many Sacramento homeowners. Between 2007 and 2011, following the rapid rise in subprime lending, one-fourth of American families lost at least 75 percent of their wealth. More than half of all families lost at least 25 percent of their wealth with these large losses disproportionally concentrated among vulnerable populations, including communities of color and lower-income communities.

open_in_full

open_in_full

Present: Housing Crisis and the Lingering Effects of Redlining

(The Race & Place in Sacramento Report is no longer referenced after this point.)

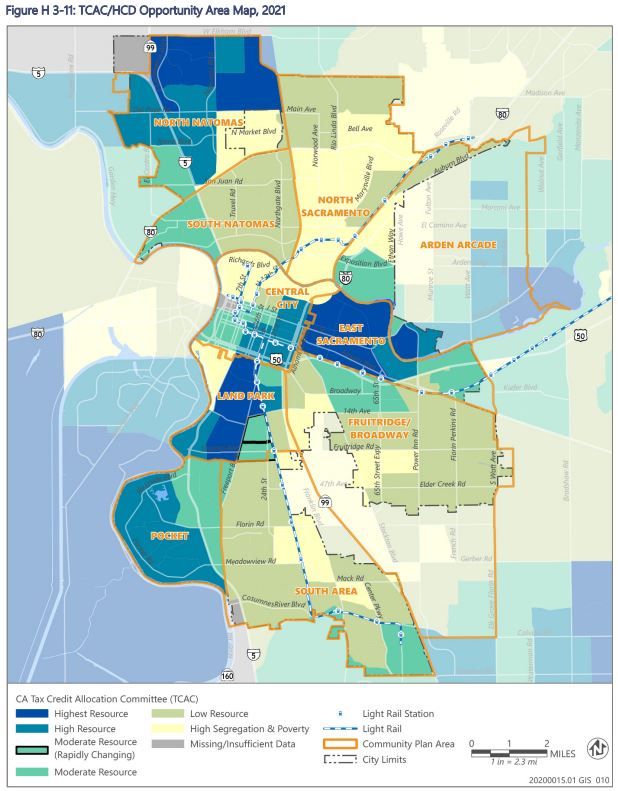

In 2017, the California Fair Housing Task Force formed and developed an opportunity mapping tool intended to demonstrate the spatial dynamics of opportunity in every census tract.

The mapping tool identifies “Opportunity Areas” to promote private investment in affordable rental housing for low-income Californians. It also identifies which areas have the highest and lowest levels of private and public resources linked to childhood development and economic mobility. Additionally, Assembly Bill 686 was signed into law the following year, which mandates that all public agencies must affirmatively further fair housing through deliberate action to address, combat, and relieve disparities resulting from past and current patterns of segregation. In Sacramento, as shown on the TCAC/HCD Opportunity Area Map, the majority of the City is categorized as either low resource or high segregation and poverty, largely aligning with the areas of the City that were historically segregated by covenants and redlining practices.

open_in_full

open_in_full

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic spread worldwide. The resulting economic fallout magnified existing challenges faced by many including access to healthcare, open spaces, affordable housing, and more. In the weeks following the issuance of social distancing guidelines, millions of people lost their jobs, leaving many without the means to afford basic amenities and secure adequate housing. This crisis highlighted the importance of affordable housing to the well-being of all our community members.

Even though race covenants and race-based lending are no longer in practice, the effects of past practices allowed white families to more easily build intergenerational wealth, while restricting communities of color from accessing opportunity and meaningful fair housing choice.

Today, Sacramento’s neighborhoods reflect the results of decades of systemic redlining, restrictive covenants in land sales, and residential segregation. Neighborhoods such as Land Park and East Sacramento remain high opportunity areas while some of the neighborhoods that had received Downtown’s displaced residents such as Oak Park, Fruitridge Manor, Del Paso Heights, and North Highlands remain highly segregated and in poverty. This economic and racial stratification, found in cities across the nation, has been further perpetuated through the use of single-family zoning. An analysis by the Othering & Belonging Institute states that single-family zoned areas have been shown to increase racial segregation and income inequality. In Sacramento, over sixty percent of residential areas are zoned for single-family housing.

open_in_full

open_in_full

One of the reasons why many of Sacramento’s higher-resourced residential neighborhoods remain largely racially segregated is because many of the “desirable” neighborhoods remain zoned exclusively for single-unit homes, a more expensive product type. The exclusion of lower-cost housing types prevent lower-income residents from moving to neighborhoods with the best parks, schools, and other desirable amenities .

Adding to the lingering social effects of redlining practices in Sacramento is the current lack of housing supply. Sacramento, like much of the rest of the State, is racing to address the current housing crisis that is making it harder for residents, especially low- and middle-income families and individuals, to afford housing. A variety of factors have contributed to the constraint on housing production over the past 50 years, including but not limited to zoning, limited governmental funding, community resistance to new development, environmental laws, , and increased construction costs.

More and more over the past couple of decades, the City of Sacramento has been focused on creating a policy environment that is leading to more housing production and is creating greater housing choice for all. In 2022, the City of Sacramento was the first city in California to earn the State’s Prohousing Designation due to the City’s commitment to housing development. The City has implemented many policies over the years to address housing constraints and continues to lay the groundwork for addressing exclusionary zoning practices. Much of this work can be found in the City’s 2021-2029 Housing Element, the City’s 8-year housing strategy and commitment for how it will meet the housing needs of everyone in the community.

Additional Resources

Please see below for additional resources:

- Race & Place in Sacramento

- Desegregating Sacramento | Center for Sacramento History

- CTCAC/HCD Opportunity Area Maps | California State Treasurer’s Office

- AFFH Data Viewer & Mapping Resources | California Department of Housing and Community Development

- Single-Family Zoning Analysis | Othering & Belonging Institute

- The Roots of Structural Racism Project Twenty-First Century Racial Residential Segregation in the United States | Othering & Belonging Institute

ON THIS PAGE